You’ve never seen anything like District 9.

Hyperbole is the root of all movie promotion, so you might read that line with the cynicism of someone accustomed to media that over-promises and under-delivers. Every Hollywood blockbuster, desperate to recoup its bloated budget, claims to be amazing. (G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra, which could replace waterboarding in military prisons as an effective method of torture, effervesces that “saving the world has never been this much fun.”)

Even tolerable summer flicks, like Fighting, have too much Tinseltown DNA to stand out in a crowded cineplex. (G.I. Joe and Fighting, for instance, both star Channing Tatum.) Jamaican audiences, raised from birth on American fare, no longer expect originality or variance, just the coddling familiarity of the Universal globe, MGM lion or Warner Bros. crest.

But the white TriStar horse is the first and last familiar image you’ll see in District 9. After that, you’re in the middle of Johannesburg, South Africa. And not some jungle-shack, studio-backlot, James-Bond version of Africa. The uncomfortable, sweltering cacophony of seven million people living and working together. The authentic specificity of Johannesburg—from the high-rises of the Central Business District to the squat shanties of Soweto—populated by its unique, post-apartheid ethnic spectrum—Afrikaner, bruinmense, immigrant. The Afrikaans-accented English. The closed-circuit cameras on the street corners. The Kwaito music.

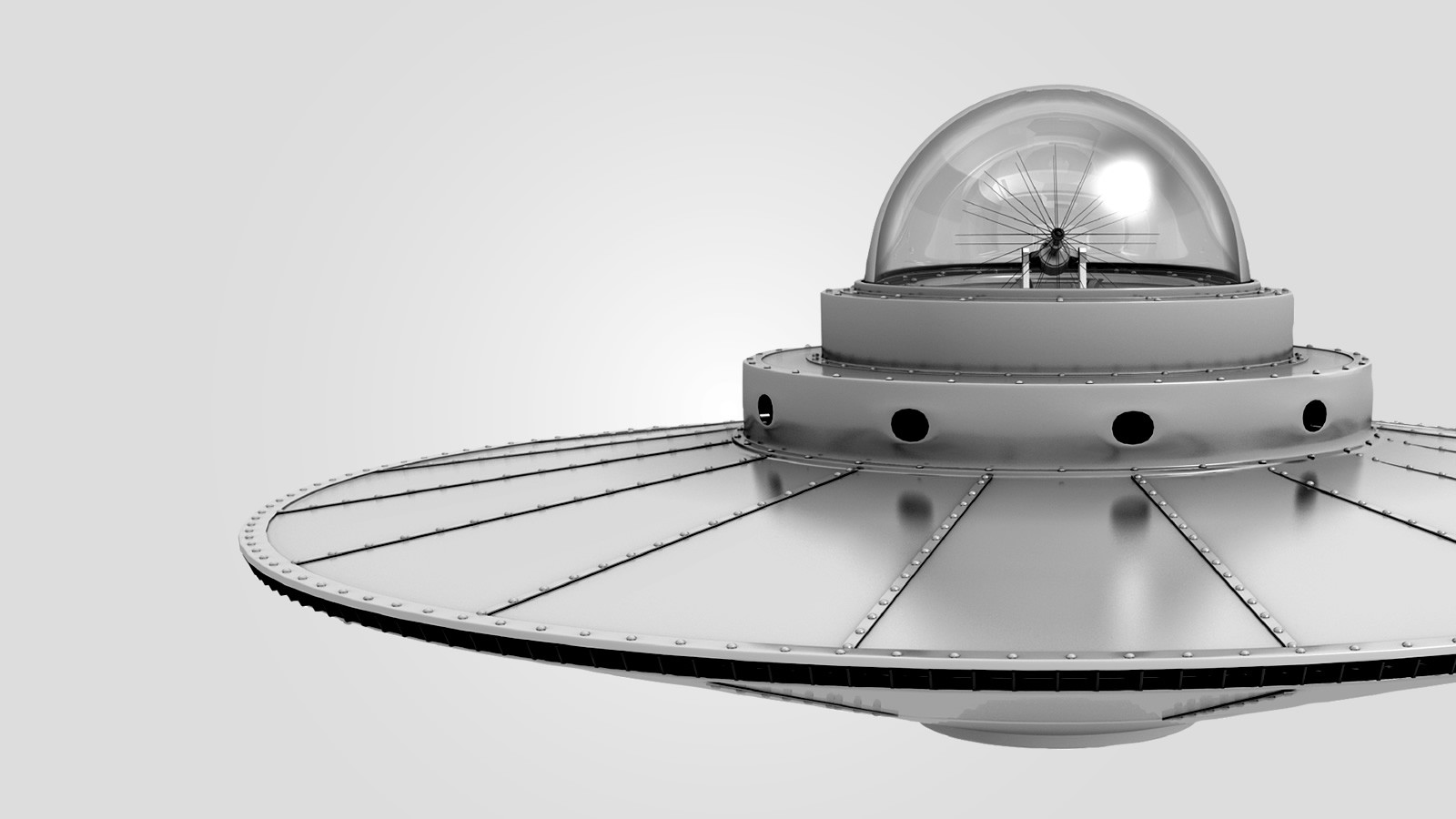

The alien mothership hovering over the city.

That’s right. District 9 is a science fiction movie, an instant classic taking its place in the galaxy of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Star Wars (1977), Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982). In the process, its young, South African writer/director, Neill Blomkamp, inherits the genre from the men behind those movies—Stanley Kubrick (dead), George Lucas (might as well be) and Ridley Scott (still going strong).

The genius of District 9 lies in how Blomkamp uses his hometown to tell a familiar story about extraterrestrials, and uses extratrerrestrials to tell a familiar story about his hometown. The aliens, having arrived twenty years ago, live in a massive fenced-off slum directly beneath their defunct ship—a temporary humanitarian effort gone permanently wrong—called District Nine. Now, they are treated like animals, or else like children, or else like savage brutes.

The government, under political pressure, is relocating the aliens outside the city. The man in charge is a meek civil employee, Wikus Van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley). Wikus is about to have a very, very bad day at work, the kind of day that makes you want to blow up your headquarters.

Blomkamp busts open the barely-congealed wounds of apartheid and rubs some Soweto dirt in them for good measure. The police freely abuse the aliens, whom they call prawns. When a discerning prawn refuses to sign his eviction notice, Wikus threatens to take his child away. City signs threaten and confine them: FOR HUMAN USE ONLY.

As a result, District 9, despite truckloads of special effects and movie trickery, feels more honest, more immediate, more out-and-out real than Sarafina (no one in District 9 has time for singing or Whoopi Goldberg). Blomkamp uses security cameras and documentary crews to heighten the it’s-really-happening aesthetic (technical term: cinema verite), tucking his computer-generated creatures into the background of newsfootage and out-of-focus citizen journalism.

It all adds up to something you’ve never seen before—the world’s first alien apartheid allegory. Go see it.