Terminator Salvation, like the war in which its characters are caught, had many ways to go wrong. It is the fourth iteration of the action franchise, by itself a bad omen (see Jaws IV: The Revenge, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, Live Free or Die Hard et al).

The 1984 original, The Terminator, and its 1991 sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, both became instant classics, not least because of their innovative director, James Cameron (who would later helm Titanic). Sequels to sequels cannot budget for innovation, however, so cheaper talent gets subbed in (e.g., Joe Johnston for Steven Spielberg in Jurassic Park III). McG, a man best known for obnoxious music videos and noxious Charlie’s Angels movies, directs Terminator Salvation.

Better men than McG have been crushed under the canonical weight of their franchises, done in by expectations or a desire to leave their mark. Joel Schumacher killed Batman & Robin after taking over from edgy A-lister Tim Burton (Batman, Batman Returns); Sylvester Stallone self-destructed Rocky IV. And the recently cancelled TV spinoff The Sarah Connor Chronicles exposes Warner Bros. as a negligent caretaker (unlike Sarah Connor herself).

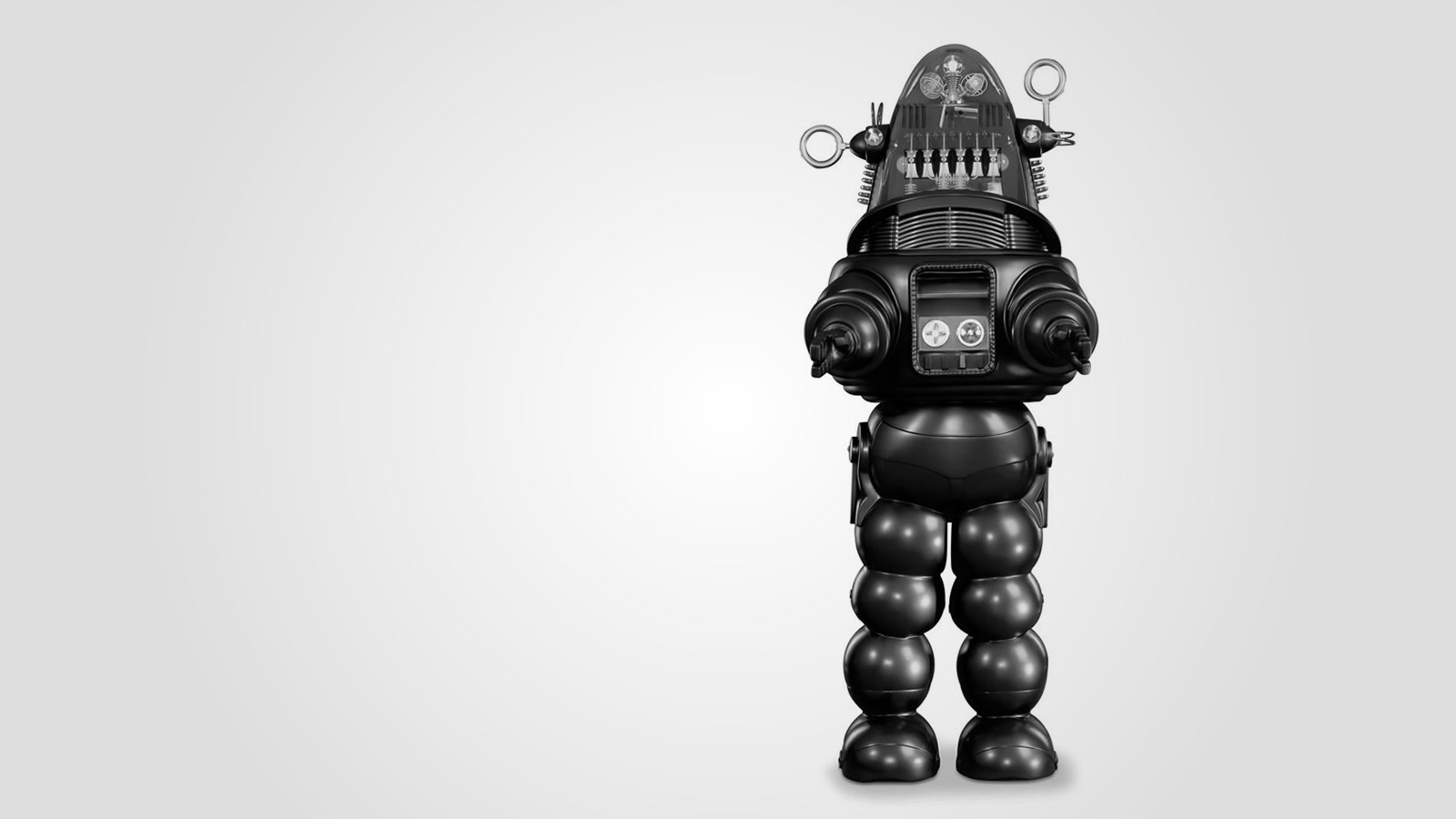

The series also leaned heavily on Arnold Schwarzenegger’s beefcake bad-guy (Terminator), turned good-guy (Judgment Day), turned both (Rise of the Machines). Now that the Austrian is too old to play an ageless robot (or, as an American politician, has become one), Christian Bale provides the testosterone as resistance leader John Connor. This makes Bale the face of two concurrent blockbuster series, Terminator and Batman, as well as Michael Mann’s upcoming gangster flick Public Enemies, risking overexposure.

But Terminator Salvation doesn’t go wrong—it shows respect towards its predecessors without being sycophantic, it rejuvenates the series for a generation that considers the muscled Arnold a punchline, and it’s a good story to boot.

John Connor has become that which the earlier films tried to prevent: de facto leader of a de facto resistance (because most of humanity has been killed). The genocidal enemy is Skynet (a kind of evil, self-aware Internet), whose unstoppable land, air and sea machines are mopping up the last bands of survivors.

In the first film, a member of the resistance, Kyle Reese, is sent back in time (to 1984) to protect Sarah Connor, future mother of John. They fall in love and Kyle unwittingly becomes John’s father. In Salvation’s 2018, the adult John must now find and protect a teenaged Kyle, yet to be sent back in time, and who doesn’t know that John, his idol, is his son.

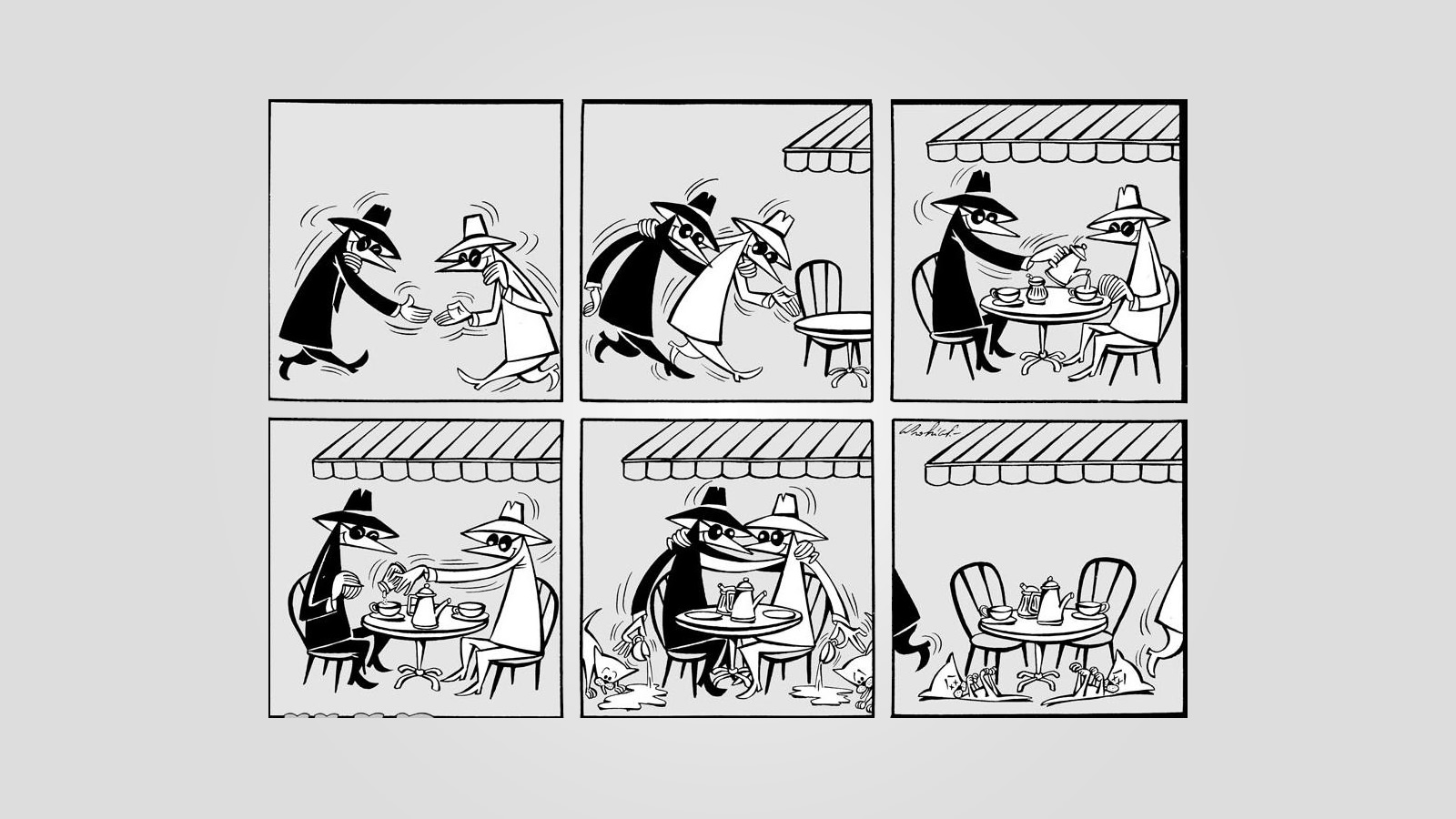

The subverted father-son dynamic forms the core of the film—as they both search for each other—around which many digital action sequences are built. Those sequences, and the film’s overall aesthetic, are heavily influenced by Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 dystopia Children of Men (in turn influenced by the 1960s French New Wave)—extended single-shot takes and a desaturation process called bleach bypass lend the footage a cinéma vérité feel (although the effect is tempered by all the killer robots).

So McG redeems himself. Christian Bale, juggling franchises, tries to become Harrison Ford. And for now, Terminator lives on.

But their future is not set. Cue percussive bombast.