The Gran Torino was an American sports car manufactured by Ford between 1972 and 1976, a long, low, wide vehicle with an aggressive grille and a large engine. It was a man’s man’s car—handsome without being conspicuous, powerful without being ostentatious. There was a gruffness about it, with a name that came from the Italian city equivalent to Detroit—Turin, or as the locals said, Torino. Today, the Gran Torino is a collector’s item, a relic, a well-crafted reminder of long-gone American automotive dominance.

Clint Eastwood, who you may have heard of, is an American actor who started out in the television western Rawhide exactly 50 years ago. He made his first fistful of dollars in a trilogy of Italian westerns portraying men with fast hands and few words. But his widest popularity came between 1971 and 1976, when he appeared in three films as Dirty Harry, a tough-and-ready cop with an aggressive streak and a large gun. He was the quintessential man’s man—strong-jawed but clean-shaven, with just enough wrinkles left in his suit and etched in his face. Today, he is a celebrated director, too old for action, a well-respected remainder of rapidly-diminishing American cultural dominance.

The comparison is invited because Eastwood’s new film, which feels for all the world like his last in front of the camera, is called Gran Torino. In it, the aged star is Walt Kowalski, a widower, a war veteran, and a psychologically wounded man. His two sons and their families have forgotten him, or try to forget him, or try to put him somewhere where they will be able to forget him. His combat duty was in Korea, the forgotten war, lost between the twin towers of World War II and Vietnam, although Walt is haunted by the atrocities he committed. He is bitter, scathing, deeply racist and desperately lonely. His only comforts are his dog and his mint-condition Gran Torino, which he helped make during his years at a Ford plant.

Oh, one last thing. He lives on a street filled with second-generation Hmong immigrants from Southeast Asia.

What follows is both simple and complicated. It is yet another retread of white guilt: Walt, and Eastwood, standing in for middle-class middle America, must come to terms with past and current sins of prejudice and discrimination. In the fifties, Hollywood made what are known as problem pictures, which dealt with “the Negro problem”. Gran Torino, on one level, is just an updated problem picture, with ethnic substitution.

But after a half-century in the business, Clint Eastwood knows how to make a movie. And he is still a captivating screen presence, even though his smooth voice is almost vanished. Through his performance and his camera, we see an unflinching portrait of a man trying to make the right choices with the wrong tools. It is hard not to view Kowalski as the logical extension of Harry Callahan, as a commentary on the costs of false invincibility and stubborn self-reliance.

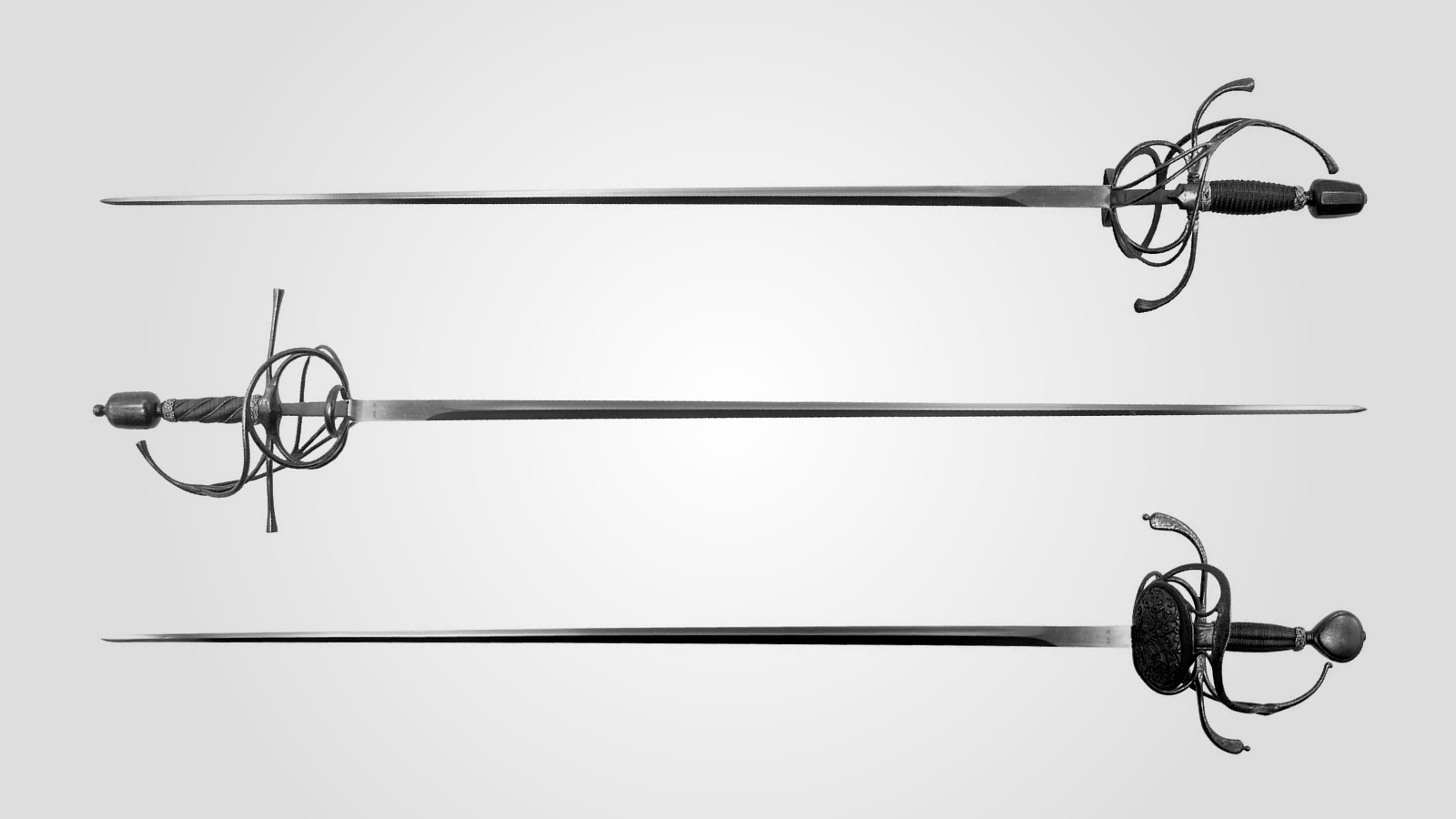

Eastwood has stripped his screen persona to its core—once again, with few words to say, but without any weapons to hold, in hands that have lost their dexterity and speed. What is left is a journey that stretches from the past to the present, from Korea to Michigan, from Rawhide to Unforgiven, a journey that ends in Gran Torino. Go take it for a spin.

Gran Torino (2008)

Directed by Clint Eastwood.

With Clint Eastwood, Bee Vang, Ahney Her.

116 minutes. Drama.