‘The greatest thing you’ll ever learn/Is just to love and be loved in return.’ Those are the last lyrics of ‘Nature Boy’, a timeless song about human nature, made famous sixty years ago by the equally timeless Nat King Cole. So simple to say — or for Nat, to sing — yet so difficult to do. Forget government bonds and collateralized debt obligations — the largest investment you can make in life is to love someone. And as the world’s stockbrokers now know all too well, without trust, your investment isn’t worth very much.

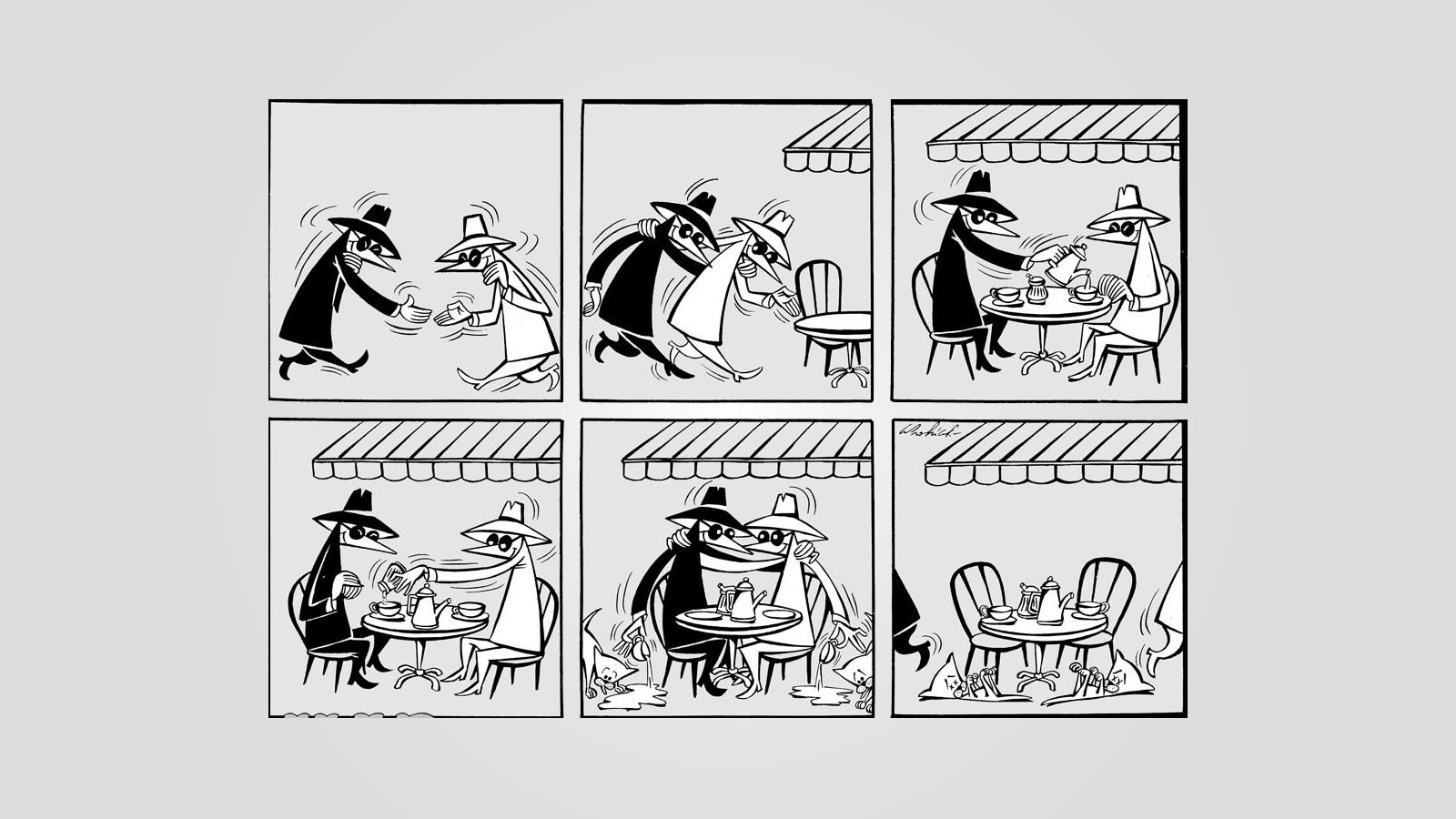

Trust is what makes relationships work, and doubt and suspicion are what kills them. Writer/director Tony Gilroy knows this, as does anyone who’s ever loved and lost. In his new movie, Duplicity, he takes the issue of trust to its logical extreme, turning his lovebirds into actual spies, engaged in real subterfuge, guessing and second-guessing, crossing and double-crossing, too scared to commit until they know the other person won’t hurt them.

This is the man who penned three Jason Bourne film adaptations and pulled double duty on the sly thriller Michael Clayton, which means: a) he knows a thing or two about movie spies; b) he likes writing for Hollywood’s leading men; and c) expect complications. Duplicity gives us not Matt Damon, not George Clooney, but Clive Owen as star hunk, and Julia Roberts for him to chase. Owen is Ray Koval, formerly of British intelligence, and Roberts is Claire Stenwick, formerly of American intelligence. If the set-up and the names sound like something out of a Raymond Chandler novel, it’s because Gilroy is head-over-heels in love with the pictures Hollywood used to make sixty years ago (back when Nat was king).

Chandler’s most famous character, hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe, was played most famously by Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep (1946). Bogart owns the screen, slouching around in tailored suits and cigarette smoke, and the camera lingers on his face as much as on his very young, soon-to-be very famous costar, Lauren Bacall. Like Duplicity, the dialogue is honed and shorn to fine-edged perfection; the characters fall in love by trading barbs.

Duplicity is set in New York (along with Dubai, London, Miami and Rome), the world capital for the world’s capital, which is why our spies are there — they are working for warring conglomerates. The second time we see Clive Owen, he is striding down a Manhattan sidewalk, and he fits the city like a comfortable leather shoe. He brings to mind that other suave, cinematic Brit who made New York his onscreen own — Cary Grant. Both men seem made for their bespoke gray suits, instead of the other way round. They belong to us, larger-than-life, every man’s exemplar, every woman’s dream.

Even Claire Stenwick’s name is homage to a Golden Age star, Barbara Stanwyck. She was one of the first femmes to be fatale, in movies like Double Indemnity (1944). Julia Roberts doesn’t duplicate Stanwyck’s cocktail of sin and seduction, but she’s still a tall drink of water. Like Lauren Bacall, Barbara Stanwyck, Grace Kelly, or any of the enduring, luminescent American actresses, Julia Roberts is irresistible, whether wrapped in bed sheets or strutting across an Italian courtyard.

Ultimately, Duplicity is a love story enthralled by love stories, a romance written by a hopeless romantic, who longs for a time when the movie never ended, when you couldn’t tell where the character stopped and the movie star began, where you could trick yourself into believing you were really watching Clive Owen and Julia Roberts fall in love. Duplicitous? Definitely. But in the end, so worth it. Just like, well, just like Nat used to sing — ‘Then I could say, “Baby, baby, I love you”/Just like those guys in moving pictures all do.’

- Duplicity

- Directed by Tony Gilroy

- With Clive Owen and Julia Roberts

- 125 min

- Romantic comedy