This is how it usually works in America — little movies have big ideas, and big movies have little ideas. For little movies with big ideas, think Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape (1989) or Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) or Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000), respectively tackling voyeurism, addiction and memory. For big movies with little ideas, consider Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Twelve (2002) or Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain (2006) or Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins (2005).

Little movies with big ideas are easy to love, and big movies with little ideas easy to hate. High art, low art. Simple. So when a big movie tackles big ideas, as in The Matrix (1999), Wall-E (2008) and now Surrogates, it’s a little disorienting.

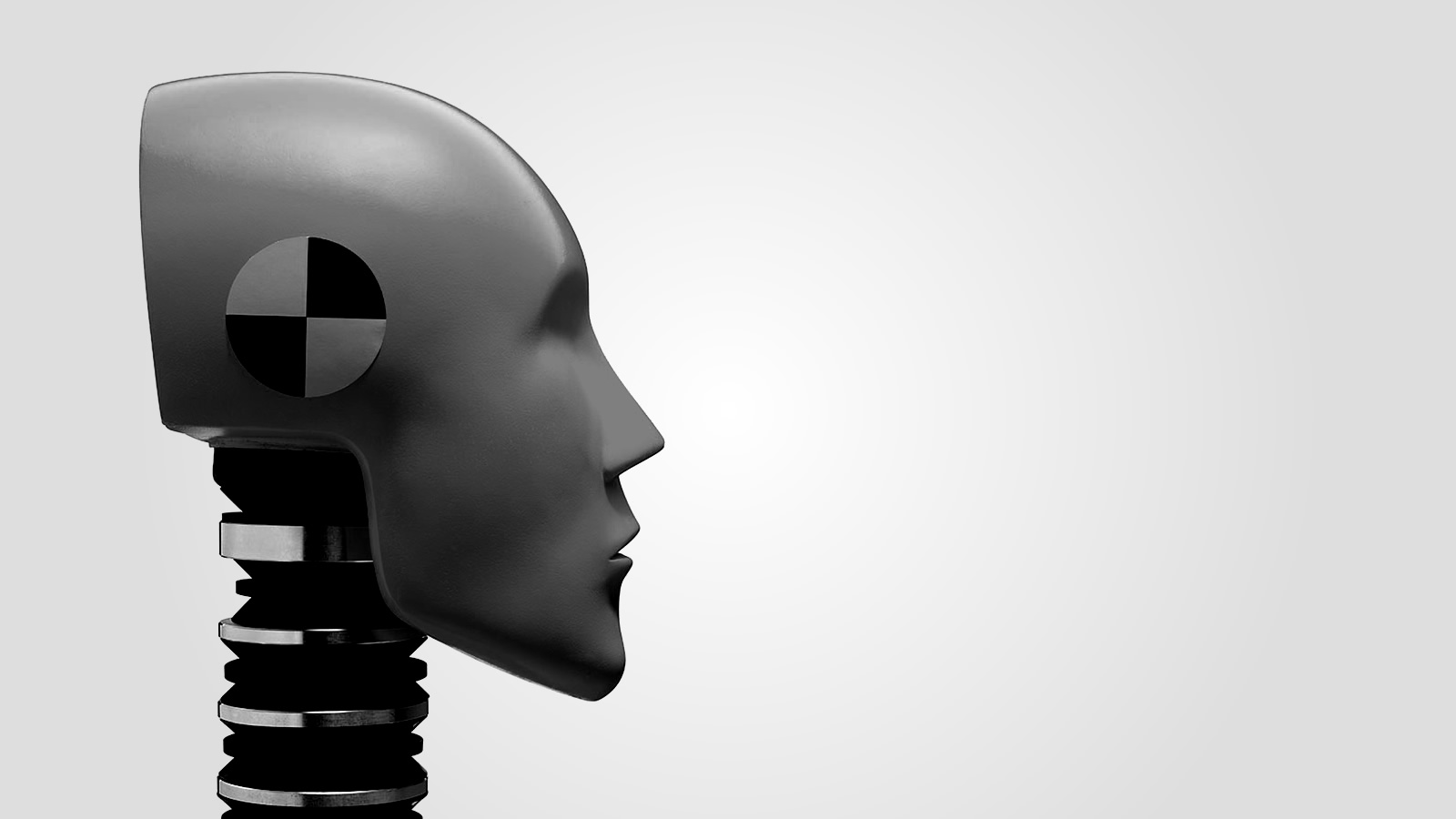

Feeling disoriented is intrinsic to Surrogates, which extrapolates advances in prosthetic limbs, along with our current penchant for creating virtual selves, to a time when everyone navigates the world via humanoid-robot versions of themselves. Just like the Internet, everyone makes their alter ego more attractive than in reality. Living vicariously through their beautiful surrogates, people experience the upside of life — like sexual promiscuity — without the nasty downside — like viral diseases. Fail-safe mechanisms prevent extreme pain — running into a bus, for example — from transmitting to the operator.

The real upshot of surrogacy, however, is that societal evils and violent crimes have all but disappeared (since all the real people are ensconced at home). No racism, no sexism, no murder. Bruce Willis plays Tom Greer, an FBI agent without much to do until he grabs a rare homicide. His investigation provides the narrative arc for Surrogates; the emotional arc stems from his ambivalence towards the technology.

The big idea being tossed around (while Greer gets tossed around) reflects that ambivalence. One of the central tenets of post-industrial societies, and the driving force behind much of the global economy, is that newer, better technology inches us towards a more perfect world. Apple unveiled newer, better iPods in September, as they did last September, as they will next September. Email, then instant messaging, then texting, and now Facebook provides newer, better ways to connect with anyone you’ve ever known. Your computer, if you’re reading this on one, is already obsolete.

All of which is supposed to be unequivocal good news, allowing us to do more while doing less, and work smarter, and other productivity clichés. You probably have an iPod, and a Facebook account, and a computer. Surrogates asks, at what cost? In the film, the cost is clear — without actual contact, people have forgotten, or lost, an essential part of their humanity.

One of the cleverer aspects of Surrogates is how it visually represents that loss by flipping a Hollywood convention. From its opening frames, the film is filled with extraordinarily fit, beautiful people, the kind of anatomical exceptions American movies are known for. Except in Surrogates, they’re everywhere, a relentless inundation of plucked eyebrows, chiseled chins and tucked tummies. You’re so sick of seeing perfect breasts that whenever someone unplugs their surrogate and stands up, their imperfections, their sheer ordinariness — mussed hair, dimpled skin, fatigued faces — becomes stunning.

Of course, plot holes abound, the heroes are white, and things work out in the end. But for a highly imperfect, ordinary big movie, Surrogates is a little, well, appealing.

- Surrogates

- Directed by Jonathan Mostow

- With Bruce Willis, Radha Mitchell and Rosamund Pike

- 89 min

- Action, Drama